Originally published on the GDS User Research Blog

More and more teams across government are putting user needs first and the demand for user researchers is high. In some parts of government, people who haven’t had any experience doing user research have now taken on this role. If you’re one of those people, this blog post is for you, and for your managers.

Welcome aboard

The first thing to say is, welcome aboard! Many of us think that doing user research is a rewarding career.

It’s exciting to see the user research capability within government growing and maturing, and we hope you’ll help us shape it in the future.

More to it than meets the eye

User research may seem pretty straight forward – find some people and ask them what they think. How hard can it be?

As with most things, you’ll find there’s much more to it than first meets the eye. Being a good user researcher is a craft, there’s much to learn and it takes plenty of practice.

Many of the researchers in my team have more than 15 years user research experience. They’ll be the first to say: “There are still things I’d like to be better at.” We’re all still learning, everyday.

So, get stuck into learning your new craft with vigour. Don’t simply do what the person in charge of your project tells you to do. Very often, they don’t know much more about user research than you do.

Here are some tips to help you get up to speed as quickly as possible so you can bring the real value of user research to your team.

Things you should read

If you’re new to user research, there are lots of quick, easy-to-read books that’ll get you off to a great start.

The essentials

Steve Krug wrote two books that every user researcher should almost know by heart.

- Don’t Make Me Think (give it to everyone in your team)

- Rocket Surgery Made Easy (about usability testing)

Read a couple of these…

Choose one of these books as a good and fast introduction to how to approach user research in projects. They’re both great books.

- UX for Lean Start Ups by Laura Klein

- Just Enough Research by Erika Hall

These books will help you with the all-important techniques for facilitating user research sessions. You should read at least one of these.

- Interviewing Users by Steve Portigal

- The Moderators Survival Guide by Donna Tedesco and Fiona Tranquada

- Interviewing for Research by Andrew Travers

Invest in these books…

AÂ bit more of an investment in terms of time and money, but these books will give you a really thorough insight into how good user-centred design should happen.

- Designing for the Digital Age by Kim Goodwin

- About Face: The Essentials of Interaction Design by Alan Cooper, Robert Reimann, David Cronin and Christopher Noessel

Every user researcher worth their salt has also read…

The Design of Everyday Things by Don Norman. You’ll never see the world in quite the same way again.

Things we’ve written – you should read these too

There’s a lot of useful guidance on the GOV.UK Service Manual.

Plus, some blog posts you should make sure you’ve read:

- User research for govt: 8 strategies that worked for us

- Doodles on why doing user research in the right place matters

- Anatomy of a good sticky note

- 6 case studies: using research and data to improve a live service

- Sample size and confidence – how to get your team to trust qualitative research

- Including people with low digital skills in user research

- User research not just usability

- How we do research analysis in agile projects

- It’s user research, not user testing

There’s your ‘homework’. It’s a great place to start, but there’s more you can do.

Find your tribe

There’s an active community of user researchers in the UK government. We talk on email and we get together at meetups where we learn stuff, do show and tells, ask questions and share knowledge. Everyone learns as a result. If you’re doing user research within the UK government, you should join the community.

Find a mentor, apprentice yourself

Make sure you work with someone who’s an experienced user researcher. This will make the biggest difference to your progress.

Ideally, your organisation will only hire people with no experience if they already have people who have lots of experience and who can mentor and support you.

Sometimes you do find yourself without much support. If that happens, there are two things you should do:

- Ask the organisation to hire an experienced user researcher. Even hiring an experienced contractor to work with you for a few months will make an enormous difference in your ability to develop as a user researcher. If you can get someone like this on the team, spend as much time with them as possible. Watch what they do, have them watch you and give feedback, ask them lots of questions about what you’re thinking of doing and why they’re doing what they’re doing. Be like a sponge.

- If you can’t get someone with user research experience into the organisation, use the network to find someone else in government to mentor you. We’re a pretty friendly bunch who want people to do well, and do user research well. Ask a good user researcher if you can shadow them a few days each month, and if they can visit you and give you feedback on what you’re doing.

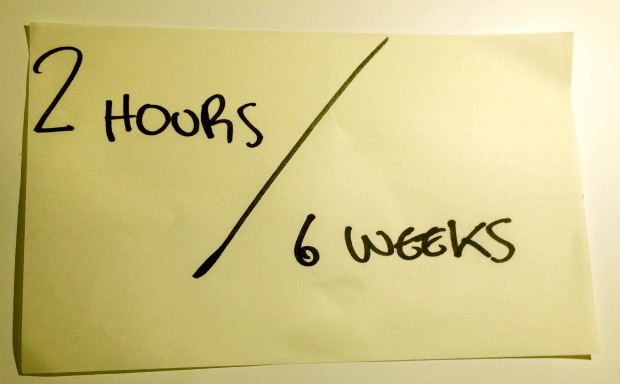

We actually encourage all user researchers – even the experienced ones – to spend 2 hours every 6 weeks watching other researchers or being watched. The best thing you can do is find a mentor to work closely with you. You might want to use the government user research community to do that.

Training is a good starting point

Doing a training course is usually the first thing that people think about. Training is good, but it’s just a starting point, it doesn’t mean you’re really equipped to take on the role without support.

You don’t have to be the expert on users

Probably the most important thing to remember is that it’s not your job to be the expert on users. Rather, it’s your job to know the techniques that will allow your entire team to become expert in what users need – and need us to do – so they can easily interact with government. User research is a team sport.

And last but not least, enjoy!